Trump hush money trial after Week 1: Fees, favors, and a tabloid publisher

Loading...

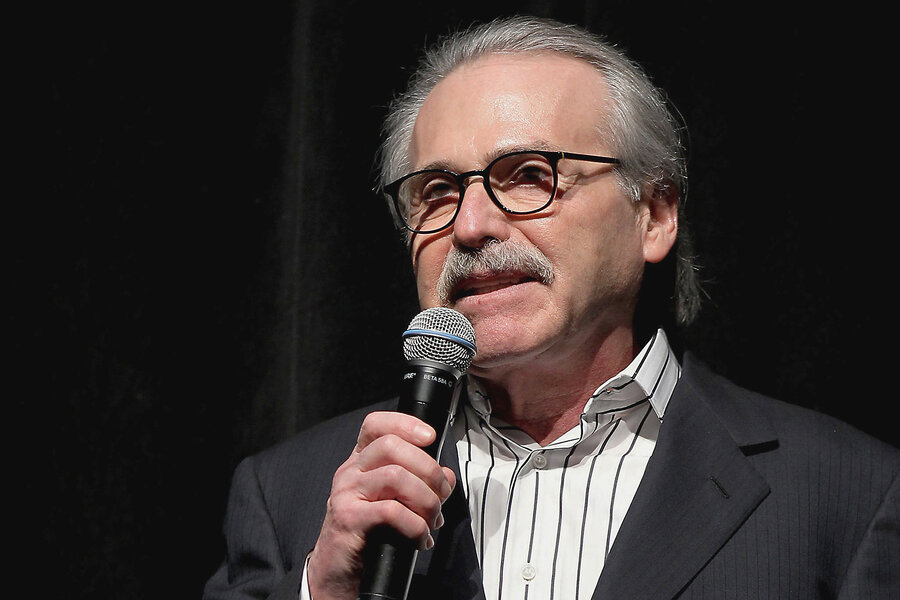

In July 2017, then-President Donald Trump asked National Enquirer publisher David Pecker to a White House dinner to thank him for help with his 2016 presidential campaign. As Mr. Pecker walked out, his host asked about Karen McDougal, a former Playboy centerfold whom National Enquirer had paid $150,000 to keep quiet about an affair she said she had with Mr. Trump in 2006.

“She’s doing well; she’s quiet. Everything’s good,” Mr. Pecker said.

Why We Wrote This

The role of David Pecker in Donald Trump’s hush money trial has revealed how much Mr. Trump and tabloid publishing have had in common.

Mr. Pecker described this scene as part of his testimony this week in Mr. Trump’s Manhattan criminal hush money trial. If nothing else, the opening days have underscored the commonalities between Mr. Trump and the world of tabloid publishing – and how intertwined they were – during Mr. Trump’s 2016 White House run and even into his first years in the presidency.

Mr. Trump has denied many of the prosecution’s allegations in this first-ever criminal trial of a former U.S. president. A jury will determine whether the actions outlined by Mr. Pecker and other witnesses constitute an illegal conspiracy to interfere in an election.

“I wanted to protect my company, I wanted to protect myself, and I also wanted to protect Donald Trump,” said Mr. Pecker during his testimony.

In July 2017 then-President Donald Trump asked National Enquirer publisher David Pecker to a White House dinner to thank him for his help in the 2016 presidential campaign. The event was “for you,” President Trump told the tabloid boss, and he could bring friends and business associates with him to enjoy the Executive Mansion event.

As Mr. Pecker walked out after a memorable evening his host asked, “how’s Karen doing?” Both men knew “Karen” meant Karen McDougal, a former Playboy centerfold whom the National Enquirer had paid $150,000 to keep quiet about an affair she said she had with Mr. Trump over 10 months in 2006.

“She’s doing well; she’s quiet. Everything’s good,” Mr. Pecker said.

Why We Wrote This

The role of David Pecker in Donald Trump’s hush money trial has revealed how much Mr. Trump and tabloid publishing have had in common.

Mr. Pecker described this scene as part of his remarkable three days of testimony this week in Mr. Trump’s Manhattan criminal hush money trial. Step by step, he asserted that he and his company had agreed to act as Mr. Trump’s eyes and ears during the 2016 run for the presidency, identifying possibly troublesome stories prior to publication and burying them, while promoting stories damaging to Mr. Trump’s opponents.

Mr. Trump has denied many of the prosecution’s allegations – regarding hush money payments to another woman, Stormy Daniels – in this first-ever criminal trial of a former president. A jury will eventually determine whether the actions outlined by Mr. Pecker and other witnesses constitute an illegal conspiracy to interfere in an election.

But if nothing else, the opening days of the trial have underscored how much Mr. Trump and the world of tabloid publishing had in common – and how intertwined they were – during Mr. Trump’s 2016 White House run, and even into his first years in the presidency.

“I wanted to protect my company, I wanted to protect myself, and I also wanted to protect Donald Trump,” said Mr. Pecker at one point in his testimony. He was referring to his efforts to suppress Ms. McDougal’s allegations of an affair. But in doing so, he might also have been describing his long association with Mr. Trump, the real estate magnate and reality TV star who once sat in the Oval Office, and may again.

First meetings and plans for “success”

In his testimony Mr. Pecker said he and Mr. Trump first met in the late 1980s or early 1990s at Mar-a-Lago. Their friendship blossomed after the publishing executive suggested they develop a quarterly “Trump Style” magazine. With all the hotels, casinos, and golf courses that the Trump Organization owned it would be a sure success, Mr. Pecker told Mr. Trump, since it had a guaranteed distribution network.

They would meet every few months to go over cover photos and content for the magazine, he said. Then in 1999 Mr. Pecker bought the National Enquirer. Mr. Trump was one of the first to call, saying he had purchased “a great magazine.”

In the early 2000s Mr. Trump’s developing stardom on “The Apprentice” series of reality TV shows took their business dealings to a new level. Mr. Trump would send over stories about the show’s ratings, the interactions of its cast, who would be fired in the next show, and so on, according to Mr. Pecker’s testimony. It was a “great, beneficial” interaction, Mr. Pecker said. Mr. Trump got free publicity with a supermarket tabloid read by millions, and Mr. Pecker got free content.

At the height of “Apprentice” ratings, National Enquirer’s own research showed Donald Trump was the best person to put on their cover to drive reader interest. As talk of a possible Trump presidential run increased, an Enquirer poll found that 80% of its readers wanted him to be a candidate. Mr. Pecker told Mr. Trump this, he testified, and Mr. Trump boasted about it on “The Today Show” during an interview with Matt Lauer.

In June of 2015, Mr. Pecker received an email from Michael Cohen, Mr. Trump’s personal attorney and fixer. It invited him to sit in a prime Trump Tower atrium floor seat to watch Mr. Trump’s declaration of his candidacy.

“No one deserves to be there more than you,” said the email, which prosecutors displayed for the New York jury.

In August of 2015 Mr. Pecker met with Mr. Trump and Mr. Cohen at Trump Tower. They asked the tabloid executive what he and his publications could do to help the Trump presidential campaign. Mr. Pecker testified that he replied he would run positive stories about Mr. Trump, and negative stories about his opponents, and that in addition he would be the campaign’s “eyes and ears” in the information marketplace.

Following the meeting, Mr. Pecker told the National Enquirer’s East Coast and West Coast Bureau Chiefs that if they heard whispers of any developing story about Mr. Trump or his family he would like to hear about them first. That would give him time to “catch-and-kill” any potentially bad stories – purchase them, and then bury them without publication.

In October 2015, one of the Enquirer’s top editors told Mr. Pecker that he had received a tip that a doorman named Dino Sajudin was trying to sell a story that Mr. Trump had fathered a child with a maid who worked at Trump Tower.

“Absolutely not!” said Mr. Cohen, when asked about the veracity of the story. But Trump Tower records showed both the doorman and the maid had indeed worked at Trump Tower, Mr Pecker testified. Eventually the Enquirer paid Mr. Sajudin $30,000 to “take the story off the market,” in Mr. Pecker’s words.

Then the Enquirer hired a private investigator. They sent reporters to the location where the illegitimate child reportedly lived.

“And we discovered it was absolutely, 1000 percent untrue,” Mr. Pecker testified.

Mr. Sajudin remained “very difficult to deal with,” said Mr. Pecker. Eventually the Enquirer released him from his contract, allowing him to shop the story elsewhere – but on December 9, 2016, after the election was safely past.

The case of Ms. McDougal was more complicated. In early June of 2016 the Enquirer West Coast Bureau Chief received a tip that a lawyer was shopping rights to the story of a former Playboy model who alleged she had a romantic relationship with Mr. Trump for nearly a year, earlier in the decade.

Mr. Pecker developed a sense that Mr. Trump at least knew the model, due to the way he called her by her first name and spoke about the issue. Eventually Mr. Pecker said that he paid $150,000 for her story, and for fitness articles and tips she would provide to his magazines.

Asked by prosecutors if Mr. Trump wanted to bury Ms. McDougal’s allegations to prevent embarrassment to his family, Mr. Pecker said he did not think so.

“I thought it was for the campaign,” he said.

A few days prior to the election, the Wall Street Journal published the story, revealing the allegations of the affair and the fact that the Enquirer had bought it to kill it. Mr. Trump was furious, Mr. Pecker testified.

“Catch-and-kill”

Mr. Pecker’s testimony brought the story of the case right up to the brink of the key figure in the Trump campaign’s “catch-and-kill” effort: Stormy Daniels.

In October, 2016, the Enquirer heard through the same source that had provided the tip about Karen McDougal that the porn star was trying to sell a story of an encounter with Mr. Trump.

“I am not doing it, period,” Mr. Pecker told Mr. Cohen, according to his testimony.

According to Mr. Pecker, he did not want the National Enquirer associated with a porn star – WalMart was one of its biggest distributors, and the company might balk if it ever found out. Nor did he want to pay out the cash. He had not been reimbursed for the payment to Ms. McDougal, and he was becoming nervous about the campaign finance implications of the effort.

Eventually the Federal Election Commission fined the Enquirer’s parent company $187,000. In the end, Michael Cohen took out a home equity line of credit and paid Ms. Daniels the $130,000 himself. (Mr. Trump denies that he ever had sex with her.)

The prosecution alleges that Mr. Trump repaid Mr. Cohen $420,000 – the initial payment, plus taxes, plus a separate payment to a polling firm for rigging online surveys, plus a bonus – via checks disguised as payment for legal services.

These disguised checks are at the heart of the business fraud charges in the case. The jury will surely hear more about them, as well as about Ms. Daniels, in coming days.

Mr. Pecker ended his testimony on Friday by saying that he regards Mr. Trump as a mentor, and recounting that the billionaire was the first person to call him when Robert Stevens, a journalist for the Enquirer parent company, died after letters containing anthrax were mailed to multiple U.S. media outlets following the September 11 attacks.

“Even though we haven’t spoken [recently] I still consider him a friend,” said Mr. Pecker.